Second-Year Law Student Dawn Henry Wins 2023 Richard Grand Legal Writing Competition

A self-described merchant of words, Richard Grand (‘58) masterfully deployed the persuasive power of a well-crafted story in his professional career, which made the theme for this year’s Richard Grand Legal Writing Competition especially meaningful.

“As we were thinking about a topic for this year’s competition, we thought storytelling would be a great way to connect Mr. Grand’s skill with narrative and the growing conversation about the use and ethics of storytelling in law practice,” said Assistant Director of Legal Writing and Clinical Professor of Law Tessa Dysart.

Students were asked to write a personal essay describing how the use of story or storytelling has affected or influenced them or someone they know.

“In the legal writing discipline, the growing Applied Legal Storytelling movement studies the use of narrative and story elements in the practice of law,” said Dysart. “Scholarship in the area examines topics ranging from the techniques effective legal storytellers use, to the cognitive science behind why stories persuade, to the ethics of using elements of story to persuade legal decision-makers. At the same time, several popular documentaries and podcasts delving into criminal justice topics have sparked debates about the outsized influence of storytelling on the perception—and sometimes distortion—of the truth.”

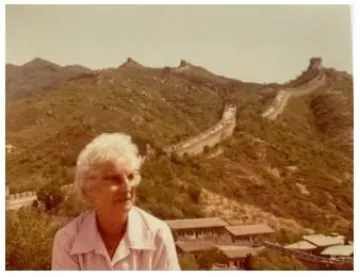

Second-year law student Dawn Henry won first place with her essay on how her childhood discovery of an old photograph of her Aunt Izzy in front of the Great Wall of China encouraged her own passion for independent travel and adventure. Henry vividly recalled a black-and-white image of a confident Aunt Izzy dressed in a tailored tweed suit with immaculate white gloves and a structured handbag. After drafting her essay, Henry contacted her mother to ask about the photograph, only to discover that the image was not entirely as she had remembered. The following excerpt is the epilogue from the winning essay:

This morning I texted my mother to fact check something: I wrote an essay about the stories we tell ourselves. I know this is an odd question, but do you remember what year we went to the family reunion at Aunt Izzy’s turkey farm in Florida?

A little later she replied: The only thing Dad and I remember is it was at the Gerard Turkey Farm in Framingham, MA. One of Grandpa’s sisters was married to Mr. Gerard. We don’t think it was Aunt Izzy’s house. You must have been very young at the time.

Interesting. I tell my mom that I would love to see that picture of Aunt Izzy at the Great Wall of China. I tell her: It’s in the old photo album we had. It had pictures of us, but there were also some loose pictures in the back. That’s where the Aunt Izzy photo was if I remember correctly.

While I wait for her to find it, I poke at the memories in my head. I envision the photo, the conversation at the turkey farm, the brooch. I am confident they are part of the story I told in my essay. Yet doubt nags at the edges of my childhood memories.

Eventually mom replies: You have a good memory! And there it is on my phone: the photograph of Aunt Izzy at the Great Wall of China.

Only I don’t have a good memory. Not at all.

There’s no denying this is the photo. The Great Wall of China authenticates the image just as much as the photograph’s location in the back of that old album.

But the image is in color, not in black and white. Aunt Izzy is a lot older than I remember, and there’s no tweed suit…no white gloves, no sturdy handbag. And she’s looking off to the side of the camera, not proudly and confidently at it.

I contemplated deleting my essay. Was I even telling a true story anymore? Instead, I shut the laptop and went for a walk.

Later I came back and looked at my essay again. I realized I was still telling the true story of the story I’d told myself about Aunt Izzy—just not the one I’d set out to share. The essay wasn’t finished. I wrote this epilogue to finish it.

Aunt Izzy was a story I told myself based only on an old photograph, a single ten-minute meeting when I was eight, and a chipped brooch. She was an idea I held on to, representing something I couldn’t even name as a child. She inspired me. She encouraged me. She made me more.

But the story I told myself about Aunt Izzy wasn’t really about her at all. It was about me: what I recognized in myself but couldn’t identify or wouldn’t dare name as a child, a teenager, a young woman. A wildness. A rebelliousness. A need for more. To see more and do more and be more.

So this is still a true story about the stories we tell ourselves. I was just never really telling her story at all. I was telling mine.

The three additional finalists were:

- Christopher Dziadosz (MLS)—Second Place

- Savannah Merchant (MLS)—Third Place

- Karen Jacquez (1L)—Honorable Mention

Judges for this year's competition were:

- Edna Aguirre, Director of Development at the Arizona Center for Women’s Advancement

- Judge Stasy Avelar, Maricopa County Superior Court

- Brooke Davis, Actress, established the Barry Davis National Trial Team in honor of her late husband

- Tim Eigo, Editor, Arizona Attorney Magazine

- Daisy Jenkins, Author, and attorney

About Richard Grand

The Richard Grand Legal Writing Competition was created by the late Richard Grand, a 1958 alumnus of University of Arizona Law who drew inspiration from art throughout his life and legal career. He often compared closing arguments to jazz, and he likened the “spark” great actors light in the imaginations of a theater audience to the connection a skilled trial lawyer has with a jury. He and his wife, Marcia, were avid art collectors who supported local Tucson artists, and many of their ongoing philanthropic endeavors support the arts.

A self-proclaimed "merchant of words." Grand began his practice as a deputy county attorney. After that, his practice was limited to representing plaintiffs. On more than 100 occasions, he obtained either a verdict or settlement in excess of $1 million.

In 1972, Richard Grand founded the Inner Circle of Advocates, which is limited to 100 lawyers in the United States who have completed at least 50 personal injury trials and have at least three verdicts in excess of $1 million for compensatory damages. The Inner Circle still exists today.